A cog in the machine

10th November 2020

It is natural for a learned society to want to engage with innovation – especially when there is a clear and present issue or problem that chemical engineers have the necessary skills to help to solve.

This is not only the case during a pandemic, it is just as true when it comes to addressing climate change, water supply, improving the nutritional value of food, or considering the sustainability of a particular process.

Of course, we want to help. Members want to engage, and employees want to support those members to make sure collectively we get the best possible outcome.

To make it a smooth experience, it is important that the role, remit and the limitations of a professional institution in this process is well understood by all.

IChemE's role

As a learned society, IChemE’s role is to promote the art and science of chemical engineering in all its forms. We do this in a number of ways including by providing a platform to connect people and to facilitate information exchange.

Our overriding mission, in line with our Royal Charter and our charitable purpose, is to benefit the community at large – in other words, we act for the common good.

This means that when supporting innovation and problem-solving, IChemE’s role is that of the impartial convenor, the matchmaker between those with a problem and those who may have a solution, and the supplier of general information.

A trap to be wary of here, is being lured into the role of consultancy. A consultant is paid for their professional knowledge and will offer their client advice on how to proceed. A consultant will also have a written contract for each project which sets out the limits of their accountability, and professional indemnity insurance to cover any issues that might arise regardless.

Our overriding mission, in line with our Royal Charter and our charitable purpose, is to benefit the community at large – in other words, we act for the common good

IChemE, as an organisation of volunteers, cannot act in this way. When there are several potential solutions to a problem, we can only set out all options, with their pros and cons, without making a particular recommendation. It is for the party receiving this information to make their own decision – and to shoulder the risk in case that decision, in hindsight, was the wrong one.

Some charities, such as Cancer Research UK, are established to conduct research. IChemE is an educational charity and is not set up to carry out any research or develop products. We also cannot procure the goods that would enable others to research or produce goods. We can, however, make the links to companies who can do these things.

Our indemnity insurance covers all volunteers working on our behalf (members and non-members alike), provided that:

- Members in a position of responsibility, such as leading on an activity, are selected by a suitable person to ensure they have the right skills and knowledge to do the job they’re asked to do.

- IChemE employees or trustees maintain continuous oversight of the work being undertaken, normally through direct staff support to the project.

- The project leaders provide regular reports on their activity and progress to the appropriate member committee, such as the Learned Society Committee.

The innovation cycle

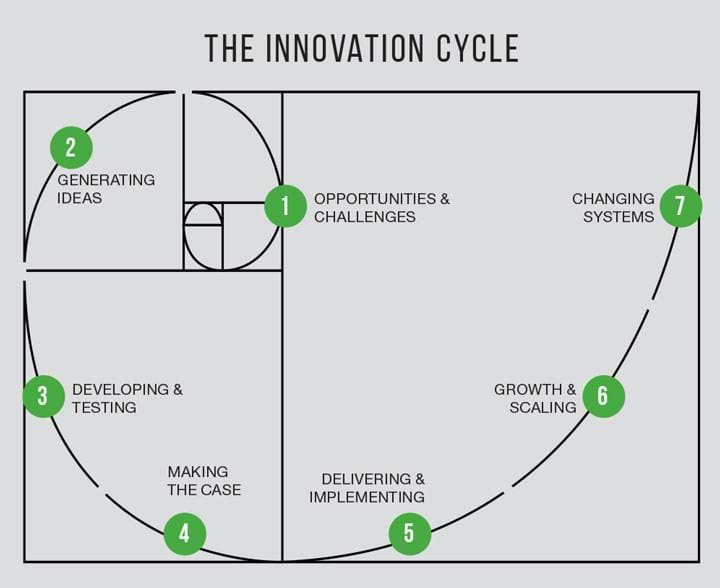

Various models have been drawn up to illustrate the innovation cycle. One way of looking at it is the Development Impact and You toolkit drawn up by the innovation organisation Nesta.

Most projects, particularly those driven by a specific problem, will start with reviewing the opportunities and challenges, or identifying the issues within the particular problem that chemical engineers can help with.

Next would come brainstorming of how chemical engineers might help – which can also involve reaching out to suitable partners, when it’s recognised that chemical engineers alone don’t have all the answers.

IChemE, in its role as honest broker and with its ability to reach far and wide into many industries and areas of expertise, is very well suited to working on and leading in these first two stages.

We can also support activities in the third stage, which is to develop and test the ideas that have been generated further, though the leadership for the project at this stage should already have moved to a partner organisation.

Once the project enters stage four – making the case for a particular solution, effectively the start of the commercialisation stage – IChemE needs to step aside, as pitching for specific solutions and developing them further does not sit well with the aims and setup of our charity.

If individual members wish to continue their involvement, then they can do so, but it must be under the auspices of the partner organisation that has taken on the project leadership.

This also means that the complications that go along with commercialisation, such as the signing of non-disclosure agreements, will sit with a commercial partner. IChemE, when acting through its volunteers, cannot sign such documents, as our relationship with our volunteer members is not that of an employer and we cannot instruct our members as to how they should behave in this setting.

In summary:

- Stage 1 - IChemE leads

- Stage 2 - IChemE leads and identifies partners

- Stage 3 - Partner leads with support from IChemE members

- Stage 4 - Partner runs and IChemE no longer formally involved. Individual members can remain involved on a personal basis.

This article also appeared in the latest issue of The Chemical Engineer.